Have you lived in another country for an extended period where you had to speak the language that you have yet to master? That frustrating feeling of your mind and your mouth were disconnected? And that feeling of being a “fish out of water?”

That was how I felt in the first few years after I moved to the United States of America. I never thought I would speak English to work and live for the rest of my adult life.

I had started to learn the alphabet in the first year of my two-year high school. Because by then, English had become a standard curriculum in high schools and required for college entry exams. English teachers in rural China where I grew up were very scarce. My English teacher Ms. Tian had been trained to teach Russian. When the high school replaced Russian with English as a required subject for foreign language, the school had her trained in an English boot camp. Afterwards she became our English teacher. She continued taking English classes on weekends while teaching us on weekdays. Naturally, the kind of English we learned was Mute English, which only emphasized on literacy, grammar to pass exams. I developed my own method of learning: memorizing every page of the textbooks I studied, and that served me well.

English class continued to be one of the required subjects in college for the first two years. Because my major was chemistry, I was assigned to a class of Mute English. I did not know enough to care much about it. After all, I did pass my exams and earned my credits!

I did get a chance to put my English-speaking skills to the test once. While in graduate school, one time I was assigned, along with another classmate, to be the tour guide for a well-known professor Barry Sharpless (accompanied by his wife Jane) from MIT who had been invited for a lecture. We would take them to visit places like Forbidden City and the Great Wall. Barry and Jane did not speak a word of Chinese, we had to use entirely English to communicate. Every time I tried talking to them, it seemed all the English words disappeared from my head and my vocal cord froze, even though I was fairly good at reading and writing. Nevertheless, we made it work by the two of us helping each other out with broken English, and with constant requests back and forth with Barry and Jane for clarifications. Furthermore, because they had such a hard time pronouncing my Chinese name, I had to come up with an assumed English name for myself Lucy. “Lucy” would become my first name after I started my new life in US.

I never would have thought that a few years later, I moved to the US, and had to face the fact: I had to unmute my English!

I arrived in Portland, Oregon on March 19th, 1992, to join my husband of two years, Eugene, who arrived six months earlier on October 8, 1991, to start his graduate studies. It was my first time ever traveling on a plane.

Before starting the journey, I had practiced a few necessary phases well in order to survive the trip, like “I am here to see my husband,” “Can you tell me where the restroom is?” “Where can I make a phone call?” “How can I transfer to this plane.” After I had landed in San Francisco, It felt super weird to me when I heard people speak fast English everywhere and I understood almost nothing.

I remember on my flight transferring from SFO to Portland, I was the only Asian person on the plane. The stewardess had served lunch, including a carton of milk, a small packet of butter, and a dinner roll. I had no idea how to open the carton. How do I describe this thing that had milk in it?! I was too scared to ask! I was afraid I’d sound weird; people would not understand me; they would laugh at me; they would think I was stupid! I literally waited and watched how other people opened their milk container then I managed to open mine! To this day, almost every time I open a milk carton, I think about the first time I did one. It was truly a unique experience.

Let me tell you: learning to speak a second language when you are an adult is hard! During most of my first couple of years, when I had a conversation with someone, I’d do three things in my head: first, I’d translate what the other person said in my head into Chinese; second, I’d think of a response in Chinese; Third, I’d translate the Chinese response into English. Then, finally, my head tells my mouth to speak back. Boy, people talk so fast!

Few months after I arrived, one professor gave us a black and white TV to help us learn English. Every evening, I’d turn on the TV and listen to the news, which always was followed by a meteorologist’s weather forecast. While I could follow most of the news, I just had such a difficult time understanding what tomorrow’s weather would be like! Oh, I wished so much I could understand the weather forecast!

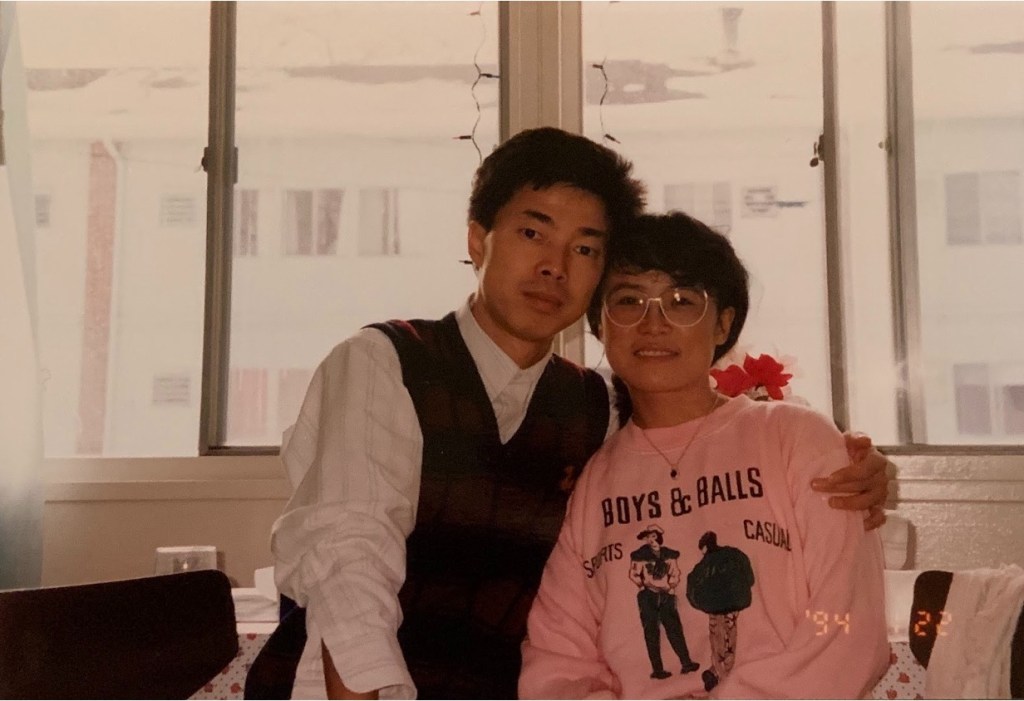

One of things I find especially hard for me to understand is the figurative meaning of some words. One time I was riding in an elevator wearing one of my favorite sweatshirts with writings: “Boys & Balls” and a picture of two boys. I had bought that shirt in Beijing. I noticed one man was looking at my sweatshirt for a few seconds and started laughing: “ha-ha, Boys and Balls” I smiled back at him politely and said nothing. I wondered why he reacted that way. To me, “Boys & Balls” just means boys playing sports. It took me another few years before I understood the other meaning of “boys and balls.” It sounds so hilarious now.

It is true that “practice makes perfect.” I have never stopped practicing over the years. I even enrolled myself in a UCSD extension course in 2012 called “Academic Writing” class to learn how to write. While my English is far from being perfect, I do feel now that the “fish is back in the water,” not a river but a tank. The tank has been slowly but steadily growing bigger over the years. I have surely fulfilled my wish of understanding the weather forecast long ago. Yes, I do dream in English.

Leave a comment